The strange history of de-extinction began long before the science

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week, for free.

On April 7, Colossal Bioscience — a company valued at $10 billion, boasting backers ranging from Chris Hemsworth to the CIA — announced the “world’s first de-extincted animal.” Using cloning, gene-editing, and anciently preserved DNA, they claimed they had brought back the dire wolf: a majestic canine that vanished from the Americas around 13,000 years ago.

Debate ensued, with most experts agreeing that Colossal had not resurrected a dire wolf. Instead, they have produced three grey wolf pups that have been genetically modified to resemble their lost relatives. An impressive feat of genetic tinkering, not a resurrection. Still, it seems momentum is building in the field of de-extinction.

From lab-grown woolly mice made to help bring mammoths back to the Siberian steppe, to spurious proclamations that T-rex leather handbags will soon be available, stories surrounding so-called “resurrection biology” are increasingly making headlines. Scientists and non-scientists alike are beginning to widely debate the ethical, political, legal, and ecological ramifications of de-extinction. Some claim it is the only way of atoning for the fact that humans have long been eradicating other lineages of life, in ways that may risk snowballing into a global mass extinction event.

But conjectures that extinct animals might be resurrected trace back to the very origin of the idea of extinction itself. As soon as people began accepting that species can disappear, they started pondering whether this could be reversed. The following is the intriguing, often surprising, history of claims that we might resurrect the zoological dead.

Created for a reason

Before the 1800s, there was neither consensus nor acceptance that entire species could forever disappear from our Universe. Instead, many naturalists actively and explicitly believed this couldn’t happen, that it was strictly impossible. They largely presumed everything in existence has been created for a purpose or reason, such that the annihilation of any part of creation, without hope of return or recompense, would introduce purposelessness and irrationality. Species extinction, at least as we now recognize it, would have seemed like a contradiction.

Reflecting on this in 1677, the English scientist Robert Plot — Oxford University’s first Professor of “Chymistry” — could see no reason why the Creator could ever be “so unmindful” as to “suffer any one species to be lost.” After all, Plot mused, so much care had been expended to “secure” all of the “works of Creation in Noah’s Flood.”

When a dinosaur bone — the distal end of a Megalosaurus femur — fell into Plot’s possession, he accordingly misidentified it as the thighbone of a human giant. Plot’s colleagues, like the botanist and zoologist John Ray, came to similar conclusions. Writing in 1688, Ray claimed not only that the number of “species in nature” is “unchangeable,” but also that “divine providence is especially concerned to preserve and secure” every one of them.

As late as 1802, the influential philosopher William Paley was sunnily pronouncing that “the loss of certain species from the universe” is a “misfortune which seems to be studiously guarded against.” Nevertheless, in the intervening decades — ever since the early 1700s — a steady stream of titanic fossil bones had been unearthed, documented, and communicated across continents: evidencing remains of creatures that undeniably no longer roam our globe, anywhere.

By the early decades of the 1800s, this triggered a sea change in the opinion of the scientific community. This was largely thanks to the work of the pioneering French palaeontologist Georges Cuvier. Studying the fossilised molars of mammoths, Cuvier had conclusively proved they belonged to a species distinct from modern, living elephants — thus establishing the reality of extinction.

Although scientists by then had widely accepted that some species had disappeared, there wasn’t yet acceptance that such absence was absolutely permanent. In the early 1800s, some people began thinking that de-extinction might happen spontaneously. While they accepted that some animals — like dinosaurs — had disappeared, they didn’t know for sure that they couldn’t return if nature was left to its own devices. For example, in 1830, the Scottish naturalist Charles Lyell — a highly respected scientist, often recognized as the founder of modern geology — speculated upon whether in our planet’s far-flung future:

“The huge iguanodon might reappear in the woods, and the ichthyosaur in the sea, while the pterodactyl might flit again through umbrageous groves of tree-fern.”

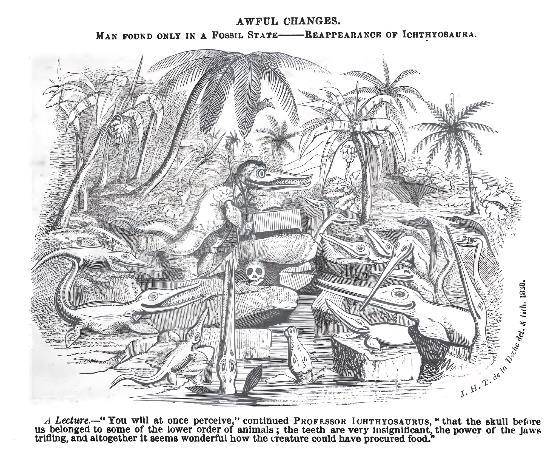

Elsewhere, in a letter penned to a friend that same year, Lyell romantically envisioned how “iguanodons and their congeners” might, at some distant date, once again stomp through England’s leafy countryside. One of Lyell’s colleagues even illustrated this scene, depicting a professorial ichthyosaur lecturing his conspecifics on the peculiar fossil anatomy of long-lost, big-brained, bipedal apes.

But, as the realization that extinct species won’t ever naturally resurrect themselves sank in, people began speculating whether we might be able to bring extinct animals back artificially.

It was around this time, indeed, that awareness of the role of humans in pushing other species to extinction was beginning to grow, alongside a swelling sense of the loss inflicted. For example, even though the last Mauritian dodo probably perished some time in the late 1600s, its human-caused extinction was only noticed as such in the 1830s.

No one fretted desperately over the dodo’s demise, but other animals were more sorely missed. One example was the European auroch: the imposing, aggressive, and wild ancestors of domesticated cattle. Overhunted for millennia and a favored game trophy of Eastern European nobility, the last auroch died in Poland in 1627. They became a hazy memory, but Cuvier’s establishment of the reality of extinction — combined with findings of auroch bones — led, in the early 1800s, to a sense of remorse for their disappearance.

In 1835, the Polish journal Przyjaciel ludu published an article suggesting that we might intentionally bring them back. “It would be an interesting experience,” the unnamed author of the article mused, to see if, by releasing “a few selected cows and bulls” back into the untamed “forests” of Poland, they might not turn back into aurochs. “Perhaps then”, the author continued, “the ancient tribe of the aurochs would return to us.”

This is likely the first ever proposition to intentionally de-extinct a species. Some have proposed that this was written by Feliks Paweł Jarocki, a Polish zoologist and friend of the virtuoso pianist Fryderyk Chopin, reasoning that Jarocki had written other articles about the lost aurochs of his homeland in the same journal. Others have also claimed this was the first proposal to conduct selective breeding — or “back-breeding,” which is the purposeful promotion of ancestral traits to bring back a precursor species — to reclaim the ancient auroch. But that’s not quite accurate. The author of the article does mention that the cattle released need to be of a “hardy breed,” but this was decades before Charles Darwin coined the term “artificial selection” and a full century before the genetic basis of inheritance was deciphered.

Instead, the author seems to be imagining that this transformation of cows into aurochs will happen effortlessly due to external, environmental factors — that is, by returning them to their primordial setting — rather than due to any internal factors of inheritance. Again, this was long before Darwin revealed how speciation actually works. Nonetheless, this does remain one of the earliest suggestions that human actions might resurrect a species previously eradicated by that very same agency.

Early visions of resurrection

As the roster of acknowledged extinct animals ballooned, the sense of loss also grew. So, too, did conclusive acceptance that deceased species will never return naturally. Writing in 1859, the prominent Victorian biologist Richard Owen was conclusive: lost species “never re-appear,” such that we must not — unlike Lyell — expect to ever find “living Ichthyosaur in the Pacific.”

Indeed, in the wake of Darwin’s theory of evolution, it became clear as to why. By the closing decades of the 1800s, the Belgian palaeontologist Louis Dollo pronounced that evolution never naturally repeats itself. An exact repetition of the countless chance couplings and encounters that forge a species is, put bluntly, statistically unthinkable.

As such, others began conjecturing whether we might bring back species through the use of technology. For example, as early as 1839, the Russian prince and poet Vladimir Odoevsky pictured a future utopian society: replete with systems for regulating global climate and high-speed transport tunnels through the center of the Earth. He also envisioned natural history reserves and museums where you can see “dry specimens” of “flora and fauna” from each of the world’s prior, prehistoric epochs — arranged in perfect chronological order.

“The collection of animals is truly wonderful,” Odoevsky writes, “so many species have disappeared or changed completely!” Quite how pristine bodies of all of prehistory’s perished creatures have been recreated is not specified, though Odoevsky’s narrator marvels at the intact “wool” on some of the extinct mammal specimens.

Photograph of fossilized dinosaur eggs found in the Gobi Desert in 1923, from The Illustrated London News.

Indeed, prior to the understanding of genetics, there could only be vague speculation upon how biological resurrection might be possible. For example, in 1932, the Hungarian science writer Desiderius Papp imagined another utopian and technologically advanced future wherein there are erected:

“…hatching houses from the cells of which living Dinosaurians were hatched for the first time from large, half-petrified eggs found in the desert of Gobi.”

Nine years earlier, the discovery of remarkably well-preserved fossil dinosaur eggs in Mongolia had made headlines — hence, Papp’s imaginative leap. These resurrected “monsters,” Papp notes, “are capable not only of growth, but also of reproduction under the expert treatment of our zoologists”. In an early echo of 1997’s The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Papp even depicted his resurrected “Dinosaurian” running loose and causing havoc in cities.

An illustration from Desiderius Papp’s Creation’s Doom, envisioning resurrected dinosaurs running amok.

Around this time, following the rediscovery of Mendel’s pioneering work, the genetic mechanisms behind inheritance were being decoded and discovered. This dovetailed with the first genuine attempts to bring extinct species “back to life” — namely, in the efforts of Lutz Heck and his brother Hans Heck.

Again focusing on the auroch, the Hecks claimed they could resurrect it through breeding existing bulls and cows displaying traits similar to their undomesticated ancestors. Where Desiderius Papp fled Europe because of the rise of the Nazis, Lutz — a German native — decided to pair with them. (His brother, Hans, was less fortunate: interned in Dachau concentration camp for four years for having married a Jewish woman.) Nevertheless, promises of resurrecting lost and pristine pasts appealed to high-ranking Nazis like Hermann Göring, who became a close friend of Lutz’s, and supported his de-extinction efforts.

Lutz Heck, on the far left, with Hermann Göring, on the far right, pondering a map of the Białowieża Forest, populated with game animals. The horn on the table may be from one of Heck’s own cattle.

Despite Germany’s zoos — where the Hecks conducted their breeding work — being heavily bombed during World War II, they nonetheless announced their success to the world after the conflict’s end. Hans proclaimed he had resurrected aurochs alongside tarpans — the wild ancestors of domesticated horses. By 1949, English-language newspapers were reporting that, “Dr. Heck has succeeded in bring back to life the aurochs,” while Spanish ones relayed that Hans himself had claimed “it will not be long” before the world witnesses “the appearance of dinosaurs, mastodon, and other antediluvian animals of which only fossil skeletons are known today.”

Of course, the Heck brothers’ selectively-bred specimens were not in fact “resurrected” aurochs or tarpans. Modern biologists consider them just new strains of horse and cattle. Since then, the development of genetic engineering and cloning has led to far more sophisticated attempts, toward the end of the previous century, to bring back charismatic animals like the Tasmanian tiger and the Spanish bucardo. All have, so far, experienced only degrees of success; never the reintroduction of a lost species into the wild.

Report on Heck’s ‘aurochs’ and ‘tarpans’, from The Illustrated London News, 1949.

Debate still rages as to whether de-extinction is even possible in theory. Many insist that any attempt will only produce, at very best, an ersatz replica of lost ways of life. As Britt Wray, who has written extensively on the topic, has explained: “it is difficult to conceive of a situation in which an exact genetic and behavioural replica of a vanished species could ever reappear.” We can create “resemblance,” but the result is ultimately a “new organism.”

A species, after all, is an intricate interplay between genome and environment, so replicating genes is not enough, and resurrecting an entire food chain or ecosystem, from top to bottom, seems unworkable. That said, when we look at how far we’ve come — in our knowledge and mastery of the world — in the few brief centuries since Robert Plot misidentified a Megalosaurus fossil for a giant’s thighbone, perhaps we should never say never. For now, however, extinction is — and will likely remain — forever.

Sign up for Big Think on Substack

The most surprising and impactful new stories delivered to your inbox every week, for free.